Ridings Equine Vets are searching for an experienced administrator to join our growing practice in Lumby, South Milford.

About Us

Ridings Equine Vets are searching for an experienced administrator to join our growing practice in Lumby, South Milford.

About Us

As many of you are aware, atypical myopathy is a deadly disease with devastating consequences for both the horse and the owner. Atypical myopathy in horses occurs when components, usually seeds or shoots, of the sycamore tree (Acer pseudoplatanus) are ingested. One of the features that makes atypical myopathy so fatal is the relatively tiny amount of toxin required to cause disease in horses. Sadly, once the toxin has been absorbed into the bloodstream, there isn’t much we can do. This post aims to explain the disease process behind sycamore toxicity and why we have seen an increase in cases in recent years.

Sycamore trees, Box Elder trees, and the unripe fruit of the Ackee tree all contain a naturally occurring protein called hypoglycin A. If a human ingests the unripe fruit of the Ackee tree, a clinical syndrome extremely similar to atypical myopathy called Jamaican vomiting sickness is caused. The Ackee tree is not indigenous to the UK, but there is a plant commonly found in this country that contains a very high concentration of this toxin – the sycamore tree.

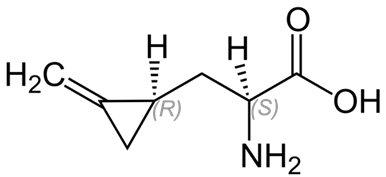

When hypoglycin A enters the body, it is rapidly broken down to the active toxin methylene cyclopropyl acetic acid (MCPA). This toxin blocks one of the key enzymes involved in the conversion of fatty acids to usable cellular energy. This prevents cells from metabolising fatty acids and making new molecules of glucose. Think of fatty acids and glucose as petrol and diesel, and hypoglycin A as a blockage in the fuel tank. When the supply of fuel is cut off, cells must start using their “reserve fuel” called glycogen. Once this back up fuel is used up, the cells have no way of obtaining a fuel source and the cell’s engine begins to shut down. This is why there is a delay between toxin ingestion and the appearance of clinical signs.

Figure 1: Hypoglycin A

The cells that run out of fuel first are the ones with the highest energy demands. One of the cells that work the hardest in a horse’s body are the muscle cells (myocytes). These muscle cells are the first victim of hypoglycin A toxicity, hence the name atypical (not typical) myo- (muscle) -pathy (disease). When the muscle cells begin to starve, signs such as sweating, muscle lethargy, muscle weakness, muscle fasciculations and tremors, colic signs, and dark coloured urine are seen. As the disease progresses, more and more cells begin to run out of fuel, resulting in worsening clinical signs. The deadliest feature of atypical myopathy is that the actions of hypoglycin A are irreversible. Once MCPA has blocked the cell’s fuel tank, there is no going back. The only hope is that the amount of hypoglycin A ingested was small enough that only some of the cells have a blocked fuel tank, and enough have been unaffected.

Recently, we have seen an sharp increase in atypical myopathy cases caused by an increase in the amount of hypoglycin A in the environment. The term “mast year” is used when a tree produces an abnormally high number of seeds. These seeds will subsequently go on to produce an abnormally high number of shoots. It is this phenomenon that has caused the higher-than-average number of atypical myopathy cases in recent years. Although the concentration of hypoglycin A in seeds and shoots varies dramatically, only a very small amount is needed to cut off the fuel supply to all the cells in a horse’s body. The only way to stop this devastating disease is to prevent horses from ingesting seeds and shoots containing hypoglycin A.

For further information regarding atypical myopathy, please click here. If you have any questions, please don’t hesitate to contact us on 07747 771 182.

Do you know your flu vaccination rules for competitions? Lots have changed recently, and different organisations have rules that do not match. In some cases some venues have different rules too!

I’ve put together a list of organisations and their current rules for vaccination - many of you will already know about these if you attend their events, but please check if you are not sure!

This is not a complete list but I’ve summarised Pony Club, Riding Club, BD, BSJA, BE and FEI below.

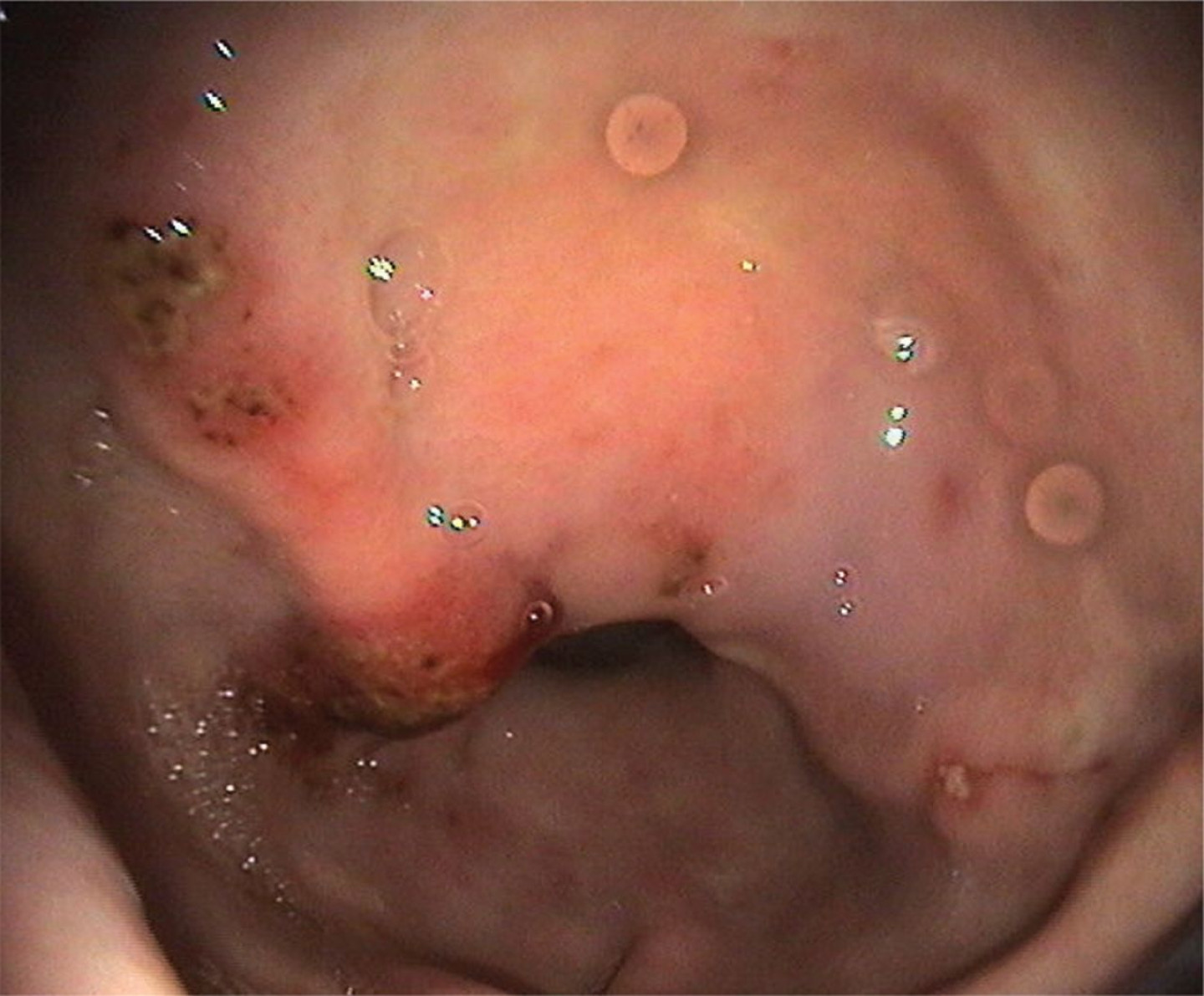

Sarcoids are types of tumour which occur in the skin. They are the most common type of equine skin tumour and have a wide range of appearances.

Common places which we see sarcoids include between the back and front legs, around the sheath, eyes or ears or on the chest or abdomen. They are common in younger to middle aged horses but can present at any age, a genetic predisposition has been noted so there may be horses that are more prone to getting them.

Melanomas are skin tumours that predominantly affect grey horses. Approximately 80% of grey horses will develop at least one melanoma in their lifetime so it is part of the course of owning a grey. Here we discuss what these tumours are, how they may develop and how to make decisions as an owner about what to do if your horse has them.

Over the last 10 years resistance to horse wormers has become more widespread. We only have a limited number of chemical drugs we at our disposal for treating worms in horses, and with no new types of drugs on the horizon it is vital we protect the efficacy of the ones we have. In this article I want to look at how resistance happens and how our management of worms may actually accelerate it...

Lets Talk All About Gastric Ulcers and Infections Skin Conditions

Over the last 10 years the way we worm our horses has changed dramatically for the better. Due to the onset of resistance to wormers in livestock and horses, we have been forced to adapt and become less reliant on blanket worming plans. Back in the 90's and early 2000's it was common to have whole yards on worming plans that involved giving every horse a wormer every 6-8 weeks.

We now know better, and thankfully the majority of owners have abandoned this practice in favour of worm egg count (WEC) tests. One question that crops up a lot, and many clients struggle to understand, is how horses in the same field under the same management conditions can have such variation in the results of the WEC tests. So I am going to do my best to explain why in this post.

Its come back to that time of year when we're just getting to grips with Christmas and New Years being over, where our bank balances are not quite where we'd like them to be and neither are our waist lines! I always find this a good time of year to have a think and remind myself what my horse needs this year and when these things need to be booked in!

Ridings Equine Vets celebrated 10 years of business in May by hosting the first ever practice Open Day!

Amy and Sarah two local riders that Ridings Equine Vets sponsors have sent us a summary of 2022 - well done to you both and we will see you over 2023!

2022 was a busy year for Team Roberts with lots of training and competing working towards our season aims...

With the eventing season just around the corner, it’s time to make some plans for the season ahead with our team of horses who range from 5 years olds starting out their eventing career at BE90 to our more advanced horses who are competing at intermediate/ 3* and we look forwards to what will hopefully be a successful 2021.

© 2018 VetsDigital Agency - All Rights reserved.